Mexico Police Uncover 150 Skulls In Cave, Unraveling Dark Secrets Of Ancient Human Sacrifice From 900 AD

When Mexican police officers entered a cave in the municipality of Frontera Comalapa in 2012, they couldn’t believe their eyes. The subterranean site in the state of Chiapas held 150 skulls and other human remains, and authorities immediately assumed it was a modern crime scene. After a decade of research, however, experts have concluded that the bones are pre-Columbian.

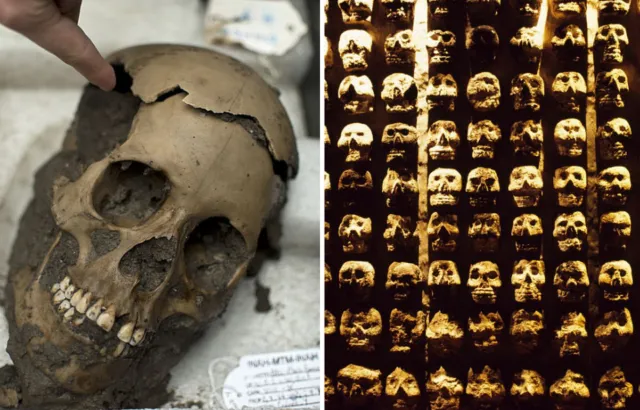

According to the New York Post, the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) announced the news on April 27, 2022. Dated to the Early Postclassic period from 900 to 1200 C.E., the skulls belonged to men, women, and infants who were ritually beheaded — and displayed on a sort of “trophy” rack called a tzompantli.

With the cave near Guatemala’s border, where human trafficking and violence are common, police initially failed to consider this as anything but a crime scene. Furthermore, pre-Hispanic sacrifice victims typically had holes bored through their skulls, but these remains showed no evidence of such damage. According to a statement released by Mexico’s Ministry of Culture, however, we now have some answers.

“Since then, analyses have been carried out that allow INAH physical anthropologists to delve into a funerary context that is approximately a thousand years old and even theorize that there was an altar of skulls, or tzompantli, in the Comalapa cave,” the statement reads.

USA Today/YouTubeOne of the only skulls with teeth discovered inside the cave.

According to Ancient Origins, police were initially alerted to the site by a local citizen who stumbled upon its macabre contents. Officers believed they had discovered evidence of mass murder and treated the site as such by cordoning off the scene, reporting it to their superiors — and collecting the skulls themselves.

“Believing they were looking at a crime scene, investigators collected the bones and started examining them in Tuxtla Gutierrez,” wrote the INAH.

When the INAH learned of this, however, years of anthropological research and physical analyses ensued. They dated the bones to 900-1200 C.E. They also realized that not a single complete skeleton was found at the scene. Only a few femurs, tibias, and radius bones were scattered about inside.

“We have recognized the skeletal remains of three infants, but most of the bones are from adults and… they are more from women than from men,” wrote the INAH. “We still do not have the exact calculation of how many there are, since some are very fragmented, but so far we can talk about approximately 150 skulls.”

The INAH was also fascinated to learn that almost all of the skulls were toothless. This paralleled the discovery of 124 skulls found in a cave in La Trinitaria in the 1980s and five others found in a cave in Ocozocoautla in 1993.

The INAH was baffled that the skulls lacked perforations on both sides, as most human sacrifices in pre-Hispanic Mexico had holes drilled into their heads to be mounted on display racks.

However, a report by the Chiapas State Attorney General’s Office confirmed that authorities had found traces of wooden sticks in the cave which were aligned in a pattern. This led the INAH to believe that the skulls had been mounted atop wooden poles rather than being penetrated through the sides.

These tzompantli racks have been long documented in accounts by Spanish conquistadors dating back to the 1520s. While the INAH currently believes that the cave in Comalapa was clearly a site of ritual sacrifice, the wooden sticks apparently used to display the skulls thereafter have naturally since succumbed to the elements.

“Many of these structures were made of wood, a material that disappeared over time and could have collapsed all the skulls,” wrote the INAH.

INAHMost of the skulls found belonged to women.

Ultimately, the INAH still has countless questions to answer. Why most of the human remains inside the cave were those of women, for instance, remains a mystery. In the end, the institute confirmed that it will continue investigating the site and its remains — with one urgent message standing out above all.

“When people find something that could be in an archaeological context, don’t touch it and notify local authorities or directly the INAH,” they wrote.